Many, many years ago, in August of 2008 to be

precise, my wife Jacqui and I received a marvellous gift: a weeklong stay, by

ourselves, on a tiny game reserve near Bela-Bela in the Limpopo Province of

South Africa.

Upon arrival, we realised immediately that the

previous summer’s rainfall had been very sparse. The bushveld surrounding us

was exceptionally dry; hardly any leaves remained on the main species of trees.

Even the hardy thorn-trees, the various Acacia

species*, had lost most of their foliage. Only the single magnificent marula

tree in the centre of the homestead we were to occupy for the next week and a

few large buffalo-thorn jujubes nearby still wore leaves that revealed shades

of green – no doubt these giants were still able to draw sufficient moisture

from the deeper water table.

Eager to unpack after the drive and to settle

down to a cold mid-morning drink, I rushed up to the main door of the compound.

As I stuck out my hand (clutching the bunch of keys I had been given), I was

startled by a lightning-fast movement above and to the left of my head. My body

froze. Whatever it was, it was rather long – not too big, but long. Slowly I

turned my head to gaze upwards and to the left. On a narrow ledge of the wall of

the compound that reached in deep under the overhanging thatched roof sat a bushbaby

(or South African galago). We two primates were each rooted to the spot, neither

one of us wishing to startle the other further.

I backed off slowly, all the while whispering to

Jacqui to come closer to have a look. With a few bounds, the bushbaby pinged

along the wall and vanished up the closest buffalo-thorn jujube. Gone!

At lunchtime two days later, I heard a family

of grey go-away-birds sounding their alarm from the top of one of the buffalo-thorn

jujubes close to the compound. I approached slowly, knowing and trusting my

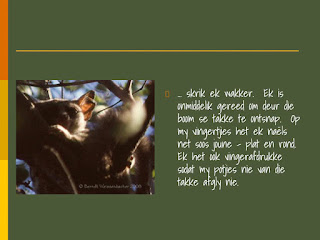

experience with these birds. Something was up. With binoculars, I scanned every

nook and cranny, every cluster of leaves of those trees. There, hidden amongst

a dense clump of foliage and protected by a patch of mistletoe was the bushbaby,

fast asleep on a branch in a patch of sunlight in the middle of the day!

My capers over the next quarter of an hour must

have seemed comical – luckily, the only witnesses were my chuckling wife, a

family of go-away-birds and a slumbering bushbaby. With deliberate but very

careful movements, I managed to fetch and lean an extendable ladder against the

main trunk of the tree in which the bushbaby was resting. With one hand free to

cling to the ladder, the other hand cradling my camera and telephoto lens, I

crept up the rickety support strut-by-strut.

Standing on the wobbly ladder 10 m above the

ground, I cradled the topmost, pipe-like rung of the ladder in the crook of my

left elbow. This allowed my left hand to support the barrel of the long lens that

I intended to use. My right hand clutched the camera. By leaning out backwards,

away from my support, I could hold onto the ladder and keep my camera's lens

stable at the same time. This was not the safest way to photograph wildlife.

I knew at the time that any images I could get

would not be great photographs; however, they would be my first images of a bushbaby

taken during daylight hours. I took the first shot. Immediately the bushbaby

opened its eyes. It shifted its body weight ever so slightly, getting ready to

leap out of harm’s way. I only snapped another three photographs. I did not

want to disturb the visitor to the compound. Obviously the dense foliage of the

trees and the overhanging thatched roof provided a rare patch of protection in

the otherwise parched and leafless, exposed bushveld. As slowly and quietly as

I could, I retreated down the ladder.

Back home, once the slide films had been

processed, I showed the images to my wife. Until very recently Jacqui had been

a teacher of Afrikaans at secondary school level. She asked if she could use

the photographs to teach her junior pupils about body parts and their

functions. That night I composed a very short slideshow on my laptop for

Jacqui's junior classes and gave her a copy. Then I promptly forgot about it.

Fast forward to the beginning of 2019. By then two

delightful little rascals, Jacqui's grandsons, had joined the family and were

of an age at which story-time had become an integral part of their daily

routine. I have always taken great delight in teaching young children about the

bush. One night, discussing with Jacqui how we could enthuse the little people

with a sense of admiration and awe about the wilderness and its inhabitants,

Jacqui mentioned the slideshow.

The next morning I trawled through my

collection of wildlife images. Since that August in 2008, I have had a few

other occasions to photograph bushbabies. I decided that I could write a short

story, posing as a bushbaby and asking the littlies to identify the narrator of

the story from clues that I would pepper throughout the short riddle.

Within a week I had written and illustrated the

first Afrikaans story, My Naam is Galago

moholi – Wie is Ek? (My Name is

Galago moholi – Who am I?). Over the remainder of 2019 and the first three

months of this year, this first mini-project morphed into a five-part series –

in Afrikaans and then translated into English – on the more common African

animals.

Every book in the series contains 14 riddles,

each narrated by one of Africa’s iconic animal species or a group of animals.

Each book asks the young (and not so young) reader to identify six mammals,

five birds, a group of reptiles and two groups of insects (except for Series 3

in which spiders replace one of the groups of insects). My own photographic

images (slightly modified) illustrate each riddle – each book in the series

contains a minimum of 162 photographs.

Thus a very brief encounter in the bushveld of

South Africa many years ago led to the birth and maturation of a five-part

series of children’s books, with 70 stories and 818 photographs in total, and

available in two languages:

Wie is

Ek? Wie is Ons? – Diere van Afrika Stel vir Jou Raaiseltjies

Who am

I? Who are We? – Short Riddles Posed by

African Animals

To find these books at your favourite eBook

seller, follow the link

* For the purists, I do know that Africa’s ‘Acacia’ species now have been assigned to the genera Vachellia and Senegalia; however, I still call them acacias – just to irritate any Australians, who, as a nation, have pilfered the name that rightfully belongs to Africa’s most iconic trees.

No comments:

Post a Comment