The great majority of visitors to wildlife reserves are watchers of large mammals, especially so the celebrated carnivores, the pachyderms and the large or rare antelope. A much smaller subset of wildlife enthusiasts is comprised of the birdwatchers who take delight in even the smallest and drabbest of the feathered folk. The birders often spend many minutes (or even hours) deciphering the minutest of differences in plumage or behaviour in order to identify the correct species to which an LBJ (little brown job) belongs. Encountered even less often are the tree-and-flower-watchers – they do exist, and it is very worthwhile spending some time in their company. An awareness and appreciation of the splendour of the flora will enrich any trip into the wilderness.

The Nature of Nature - African wildlife and environmental images, stock photography and fine art prints.

Thursday 22 October 2020

REMINISCENCES: Of Legal Eagles and Culture Vultures

The great majority of visitors to wildlife reserves are watchers of large mammals, especially so the celebrated carnivores, the pachyderms and the large or rare antelope. A much smaller subset of wildlife enthusiasts is comprised of the birdwatchers who take delight in even the smallest and drabbest of the feathered folk. The birders often spend many minutes (or even hours) deciphering the minutest of differences in plumage or behaviour in order to identify the correct species to which an LBJ (little brown job) belongs. Encountered even less often are the tree-and-flower-watchers – they do exist, and it is very worthwhile spending some time in their company. An awareness and appreciation of the splendour of the flora will enrich any trip into the wilderness.

Sunday 18 October 2020

A SENSE OF PLACE: Kruger National Park’s Mopane Country

The Kruger National Park, South Africa, remains my favourite destination for wildlife photography. In particular, I am enthralled by the more densely vegetated central and northern regions of this vast, magnificent reserve. From the middle of the park northwards, the vegetation quickly becomes dominated by mopane (Colophospermum mopane) on the flatlands. Three large rivers, flanked by thick riverine bush, cut across the flat plains. The rivers and their numerous smaller tributaries allow the growth of dense woodlands and scrublands in this part of the park.

Thursday 8 October 2020

REMINISCENCES: Why do Bullies Always Hog the Swimming Pool for Themselves?

As a four-year-old, I came very close to drowning in a public swimming pool. It is no surprise then that as a pre-teen I was always reticent to immerse myself in deep water, be it in a swimming pool, a farm dam, a lake or a stretch of river. In my early teens, I developed into a very strong swimmer and enjoyed the wild waters tremendously. Nevertheless, public swimming baths still gave me the heebie-jeebies. The reason for this apparent discrepancy was rooted firmly in the inevitable presence at public pools of a few males intent on being noticed, thereby disrupting the peace and pleasure of others. There are always bullies at public swimming pools!

Sunday 4 October 2020

UITTREKSELS UIT: “Wie is Ek?” “Wie is Ons?” – Diere van Afrika Stel vir Jou Raaiseltjies – Reeks 1

Elke

reeks bevat veertien kort raaiseltjies. Hulle word aan die jong leser gestel

deur ses soogdiersoorte, vyf voëlsoorte, twee ordes insekte en een groep

‘reptiele’. Elke raaisel is

geïllustreer met uitstekende fotos. Kom meer te wete oor elke spesie of groep

se kenmerkende persoonlikheid, eienskappe en eienaardighede deur te probeer om

die vrae te beantwoord “Wie is Ek?” en “Wie is Ons?”.

Om

hierdie boekies by jou gunsteling eBoek verskaffer te kan vind, volg die skakel

My Naam is Galago moholi – Wie is Ek?

Ek

is veral beroemd vir my springvermoë – ek klouter nie in bome rond nie, ek wip

en spring van tak tot tak, van boom tot boom. Dis hoekom ek 'n lang stert het -

my stert help my om my balans te hou. My stert help my ook om koers te hou

terwyl ek gedurende 'n lang sprong deur die lug seil. As ek op die grond moet

beweeg, omdat die bome te ver van mekaar af staan spring ek ook op my

agterbeentjies in lang, hoë boë – jy sal my nooit sien hardloop nie.

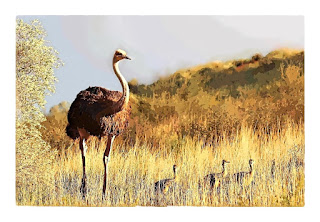

My Naam is Struthio camelus – Wie is Ek?

My

ma en pa is die grootste voëls op die hele aardbol. Omdat hulle so groot is kan

hulle ongelukkig nie vlieg nie. My ma se vere is van 'n vaalbruin kleur. Net

die vere op haar maag en sye is vaalwit. My ma lyk eintlike altyd stowwerig. My

pa spog met swart vere op sy rug en vlerke – sy vere op sy maag en sye is

spierwit. My pa hou daarvan om sy vlerke wyd te sprei en dan te wikkel; só spog

hy met sy veredrag.

Soos

jy weet vertel mense graag stories oor die diereryk. Een van dié stories is dat

ek sukkel om 'n besluit te neem en dat ek liewers my kop in die sand sal steek

as om 'n probleem op te los. Ek kan vir jou nou sê dat ek dit nooit doen nie.

Hoekom sou dit in elk geval só wees? Ek is mos baie slim en rats.

Ons is die Dag-aktiewe

Skubvlerkige Insekte van die Orde Lepidoptera - Wie is Ons?

As

ons besig is om op 'n blom rond te klouter terwyl ons nektar soek, word ons

lywe oortrek met die stuifmeel van blomme. So is ons verantwoordelik vir die

bestuiwing en voortplanting van baie plantsoorte. Die blomme self kan nie

voortbestaan as ons nie hulle nektar sou drink nie. Dit is hoe ons nog altyd

met blomme saamgewerk het – hulle gee vir ons nektar en ons karwei hulle

stuifmeel na 'n ander blom toe aan, maar altyd net van een spesifieke blomsoort

na dieselfde blomsoort.

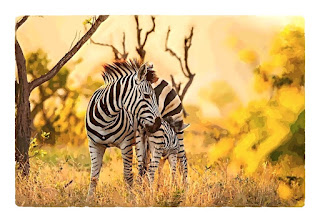

My Naam is Equus burchelli – Wie is Ek?

My

lyf is nou nog met langer hare oortrek sodat ek nog 'n bietjie wollerig lyk. As

ek ouer word sal my hare kort wees. My lyf is gestreep in wit en swart lyne. As

jy mooi oplet sal jy sien dat daar ook dun ligbruin lyne tussen die wit en

swart strepe loop. Van my kop af oor my nek tot by my skouers dra ek 'n maan

van lang, swart hare wat altyd kiertsregop staan.

Ek

het ook 'n lang stert wat met lang, swart hare versier is. Ek gebruik my stert

voortdurend om stekende vlieë van my lyf af weg te hou. Mense het altyd geglo

dat my strepe vir my 'n soort kamoeflering in die bos is – maar my strepe

verwar eintlik die vlieë wat my bloed wil suig sodat ek minder deur dié

bloedsuiers gepla word as ander wilde diersoorte.

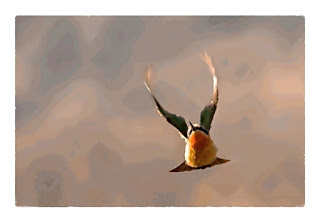

My Naam is Merops bullockoides – Wie is Ek?

Noudat

ek al baie gesels het, sal jy ook seker wil weet hoe ek lyk en wié ek is. Ek

sal eers my ouers beskryf omdat hulle kleurvoller as ek is; jy onthou dat ek

nog nie volwasse is nie. Vir voëls is my ouers van middelmatige grote – hulle

lywe is redelik lank en slank. Die vere op 'n volwassene se rug en vlerke is 'n

mooi, donkergroen kleur. Die vere aan die stert se onderkant is 'n donker blou.

Die vere op die bors asook die nekvere en vere op die kop se kruin is van 'n

ligte oranjebruin kleur.

My Naam is Phacochoerus

aethiopicus – Wie is Ek?

My

stert is lank, dun en kaal, behalwe vir 'n kwas kort hare aan sy punt. My stert

word kierts-regop gehou wanneer ek draf; so kan my familie sien waar ek

hardloop tussen die lang grasse en struike deur. Só sal my ma haar kinders nie

maklik in die bos verloor nie. Dis nou 'n puik sisteem om mekaar te laat weet

waarheen jy verdwyn het. Ek is verbaas dat nie meer diersoorte aan hierdie plan

gedink het nie.

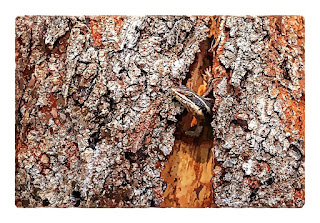

Ons is die Nie-giftige,

Vierpotige Diere Met 'n Skubbige Vel van die Orde Squamata – Wie is Ons?

Voordat

ons met ons raaisel kan begin, moet ons net eers 'n probleem uit die weg ruim.

Julle mense het ons nog altyd ‘reptiele’ genoem, maar ons was nog nooit net een

natuurlike versameling van diertjies gewees nie. Sommige ‘reptiele’, soos julle

aanhou om ons te noem, is nader familie van voëls as wat hulle familie van die

ander ‘reptiele’ is.

Dit

is eers nóú dat die wetenskaplikes agterkom dat hulle 'n fout gemaak het om ons

almal saam in een groot groep te plaas. Ons het glad geen probleem om die voëls

saam in ons groep te verwelkom nie – 'n puik en ook wetenskaplik aanvaarbare

oplossing! Die voëlkykers sal egter die stuipe kry as hulle agterkom dat hulle

nog altyd net ‘reptielkykers’ was. Wié is ons nou eintlik?

My Naam is Haliaeetus vocifer – Wie is Ek?

Ek

het ook aan die begin van hierdie raaisel gesê dat ek wêreldwyd beroemd is. Dis

nou nie eintlik ék nie maar wel my ouers. Elke dag patrolleer my pa 'n lang

gebied net langs ons rivier om seker te maak dat geen ander voël ons visse daar

sal kom vang nie. Jy sal my pa en my ma maklik sien terwyl hulle vir ure op

bome sit om ons gebied vir indringers dop te hou. My pa sweef ook gereeld in

wye kringe oor sy gebied, of hy vlieg net bo die boomkrone op die rivier se wal

rivier-op en rivier-af.

My Naam is Canis mesomelas – Wie is Ek?

Ek

is seker dat jy al 'n storie of wat oor ons gehoor het. Die mense sê aanmekaar

dat ons baie slim is, maar dat ons ook slu en agterbaks is. Ek hou glad nie van

dié stories nie. Ons is wel slim en boonop is ons baie rats. Ek dink dat daar

'n paar mense is wat dié stories versprei omdat hulle nie so slim en vinnig

soos ons is nie.

My Naam is Streptopelia capicola – Wie is Ek?

Dit

is nou al 'n week gelede dat my sussie en ek leer vlieg het. Ek moet bely dat

ek nog nie heeltemal die vliegkuns perfek geleer het nie, maar ek kan darem al

in goeie, stil weer redelik goed en vinnig vlieg. Ons kinders volg nog heeltyd

ons ouers as hulle kos soek – hulle deel ook nog baie van hulle kos met ons.

Daar is nog baie om te leer; hoe om in die veld veilig te wees en watter

kossoorte waar te vind is. Ek is opgewonde (maar ook 'n bietjie bang) dat ek

oor 'n week of so my eie gang sal moet gaan – anders as by jou mag ek nie meer

as drie weke by my ouers bly en van hulle afhanklik wees nie.

Ons is die Vinnigvlieënde

Jagtende Insekte van die Orde Odonata - Wie is Ons?

Om

die klein prooi wat ons op jag maak te kan raaksien, en om nie in iets vas te

vlieg nie, het ons reuse, saamgestelde oë. Dit beteken dat elke oog baie lense

het en nie net een soos dit by jou oë die geval is nie. Daarom sien ons enige

beweging in die veld om ons maklik raak. Ons oë is só groot dat hulle amper die

hele oppervlakte van ons koppe beslaan. Daarenteen het ons nie 'n gooie reuksin

nie; ons antennatjies, of te wel voelhorinkies, is maar baie kort. Ons kan ook

ons koppe draai omdat hulle deur 'n baie kort nek aan ons borsstukke vasgemaak

is. Weereens kan ons die hele wêreld om ons maklik fyn dophou.

Ons

is die vinnig vlieënde vername jagters van die waterkante. Om ons te sien moet

jy skerp oë hê en jy moet fyn oplet. As jy weer 'n keer by 'n waterbron soos 'n

rivier of dam 'n bietjie tyd kan vertoef, kyk uit vir 'n kleurvolle flits wat

deur die lug snel. Dít sal een van ons wees!

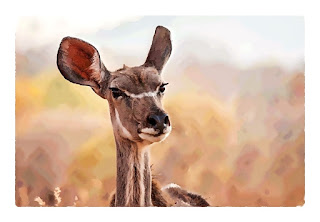

My Naam is Tragelaphus

strepsiceros – Wie is Ek?

Op

my klein koppie spog ek al met twee kort horinkies. My ma lag altyd; sy sê dis

nog nie horings nie, dis nou net kort spykertjies. Ek dink sy is 'n bietjie

jaloers want sy het nooit horings gehad nie. My pa en ooms spog met die

mooiste, lang, gekrulde horings. Hulle lyk soos spirale, 'n bietjie soos die

kurktrekker wat jou pa gebruik om 'n wynbottel mee oop te maak. Eendag sal ek

ook met 'n paar horings kan spog omdat ek 'n mannetjie is.

My Naam is Alopochen aegyptiaca – Wie is Ek?

Byna

onmiddellik nadat ek en my klein sussies en boeties uit ons eiertjies gebars

het, het my ma ons geroep om saam met haar dam toe te stap. Jy sou verbaas

gewees het om te sien dat ek só gou kon stap en selfs kon swem – al was dit net

dat ek op die water gedobber het en my pootjies gewikkel het om vorentoe te

beweeg. My ma en pa het ons veilig gehou – ons het net in 'n klein vlak

poeletjie gebly en ons mag nooit ver van die oewer beweeg nie sodat krokodille

ons nie kon gaps nie.

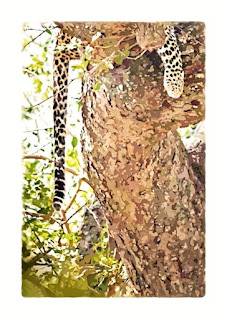

My Naam is Panthera pardus – Wie is Ek?

As

jy in die nag slaap is ek wakker en op jag in die pikdonker. Terwyl jy in die

skool sit om meer te leer, lê ek lekker in 'n sonkolletjie en rus. As die dag

warm raak hou ek daarvan om op 'n breë tak van 'n groot boom te lê en slaap. Jy

sal miskien my stert sien afhang – die res van my lyf sal sommer tussen die

sonkolle en skaduwees wat op die blare val wegraak.

Labels:

animal behaviour,

biomes,

birds,

Books to Read,

children's books,

environment,

flora,

imagination,

insects,

mammals,

photography,

reptiles,

Series,

wildlife photography

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)