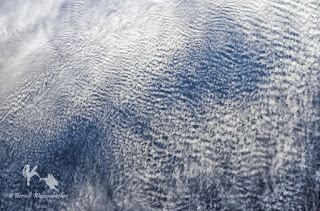

Like most

children, I was a cloud-spotter from the knee-high stage onwards. The

cloudscape above the South African veld

made an indelible impression on me. Hours on end we children would lie on our

backs, the hot sun baking our tanned faces, arms and legs, high above us

cumulus clouds suspended in the heavenly blue: Big Ears-ears, Pinocchio-noses,

old-man-faces, unicorns and other creatures and landscapes of mythopoeia. Add

to that the seemingly endless wisps and stripes of high cirrus clouds, the

towering walls of cumulonimbus castles. I imagined an enchanted world amongst

the clouds, a world higher and greater than my own down below.

Alas, in

contrast to almost all other children, my perception of the world around me has

never changed. I still seek for, yearn for, the charmed and enchanting in an

otherwise stultifying adult world. So I remain a cloud watcher, peepers pointed

skyward, still searching for my fairy queen and yet another glimpse of that

other world. Nowadays, however, looking is not enough. For me, as a

photographer, clouds remain endlessly fascinating: in constant flux, never

static in pattern or process, and especially the incessant wonderful play of

light and shadow that arises.

Special

excitement is provided by iridescent clouds. When thin cloud layers

(particularly cirrostratus, altostratus and altocumulus clouds) are present in

the sky, it can happen that sunlight shining through these clouds breaks apart

into its rainbow colours. This phenomenon is observed best when the clouds

occur in an arc of less than 20° from the sun. Since you are facing the sun,

often the light is too bright then to observe the phenomenon or to capture an

impressive image on film. It is better to photograph this singular spectacle at

sunrise or sunset, especially when the sun is shielded by other clouds so that

no light falls directly on the lens.

In general,

iridescence appears when surfaces of objects are composed of multiple layers or

the surfaces comprise a very thin film, as for example in soap bubbles or when

oil is spilt on water. In these instances, the light that impinges on the

object is reflected, not off one surface, but off several different tiers. If

the incident light originates from a single source (as is the case with

sunlight), iridescence occurs strongly since the wavelengths of the reflected

light rays coming from different layers can interfere with each other. In this

way, some wavelengths are either dampened or enhanced. With interference all

the wavelengths reflected off an iridescent object added together no longer

appear white (the total sum of all colours in sunlight), but parts of the

object now show a colour cast. The resulting spectacle depends on the angle of

view, of course.

In clouds

specifically, several processes that occur simultaneously cause iridescence. When

sunlight passes through a thin cloud layer, some light rays are absorbed; most

rays, however, are scattered by the cloud particles, so that the cloud usually

appears white. Some light rays pass between the water droplets or ice crystals

and are thus diffracted. Other rays pass through the droplets and are then

refracted and split into their constituent colours.

Whether sunlight

passes through or between water droplets, whether it is diffracted, reflected

or refracted, the light rays that finally travel towards the observer can still

cause interference phenomena. Since sunlight originates from a single (point)

source, all the light rays are still in phase with each other (even after the

many changes that have occurred); therefore, two light rays can become

superimposed one on the other to give rise to interference. With this, some

colours may cancel out; others may become exaggerated, because the different

wavelengths of light are affected differently during interference.

The result of

this long journey by the light rays through the diaphanous cloud is iridescence.

From the point of view of the observer, the angle between the cloud and the sun

must be less than 20° for this phenomenon to be visible. In addition, the

resulting colour spectacle is dependent on the density of the cloud or cloud

layer. If the clouds are very thin and wispy, the colours that appear are

washed out and indistinct; on the other hand, if the clouds are too dense,

either too much light is absorbed or the rays are scattered too irregularly to

result in iridescence. Other factors that modulate the appearance and intensity

of iridescence include the size of the cloud's water droplets or ice crystals,

the movement of the cloud and the way in which the sunlight impinges on the

cloud surface.

Cloud

iridescence is not a halo phenomenon, since the colours occur in bands rather

than in concentric rings, as is the case with halos. Iridescent clouds also

differ from the similar nacreous or polar stratospheric clouds and noctilucent

clouds. Although the physical processes involved in all these cases are the

same, iridescent clouds can be observed at most latitudes and during daylight

hours. The cloud type involved in iridescence always comprises cirrus- or

stratus-type clouds in the troposphere (the lowest layer of the atmosphere,

starting at the earth's surface and extending to a height of between 7 km at

the poles and 17 km at the equator). In contrast, nacreous clouds can only be

observed at latitudes larger the 58° from the equator. Also, nacreous clouds

are found in the stratosphere (up to 30 km above the earth's surface). In the

case of noctilucence, high clouds in the mesosphere (between 50 km and 80 km

above the planet surface) may still reflect sunlight after sunset (or before

sunrise) during very deep dusk.

So, do I still

spend time on my back these days? Of course! The only change that has occurred

is that the bones complain when I attempt to stand up after a long sojourn in

the magical, mythical realm of clouds.